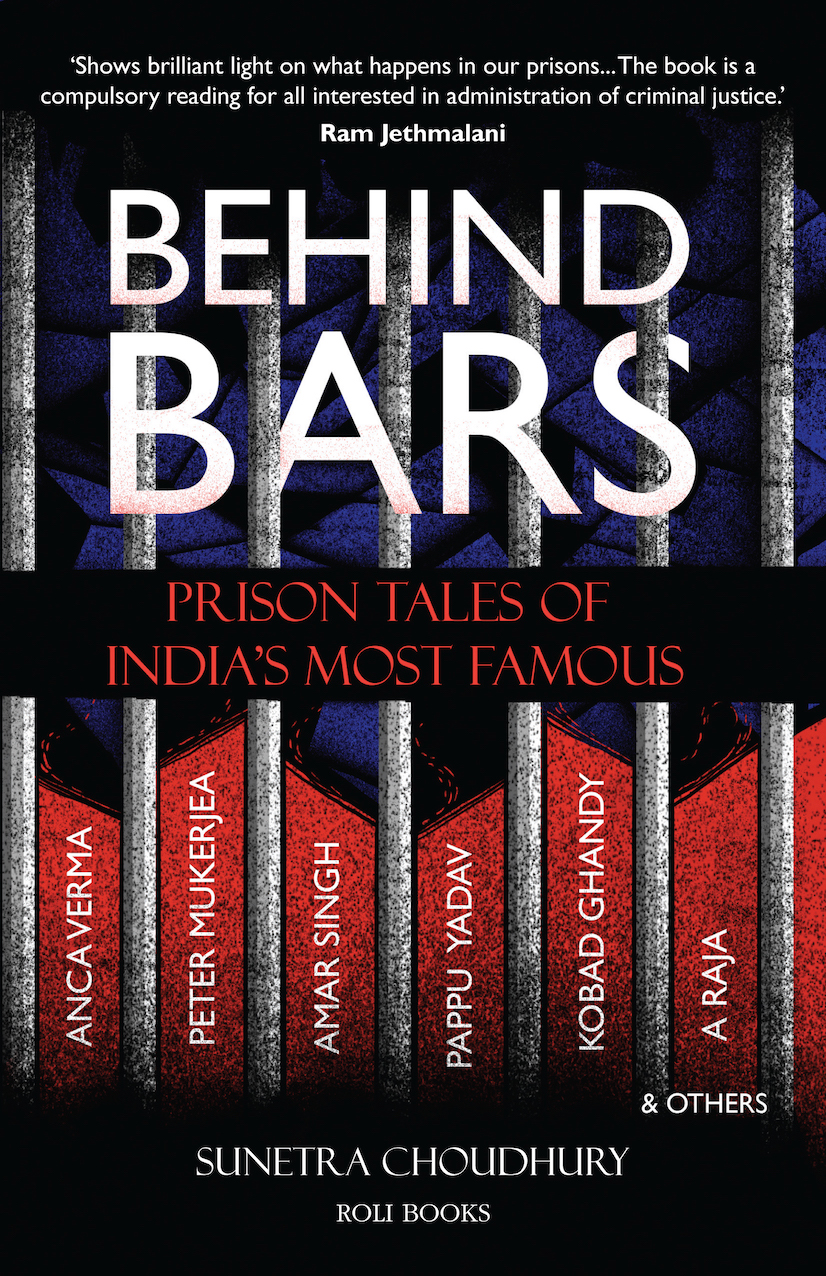

Behind Bars, written by journalist Sunetra Choudhury, is an honest and compelling account of the stories of those imprisoned in India’s prisons.

Each chapter talks about one person and his or her tryst in prison. The story is well-developed and fleshed out, right from the background circumstances that got the person into prison in the first place and the jail experiences of the ‘accused’. While all the accounts are true, the manner in which she narrates them is no different than that of a story.

For example, when she talks about Sushil Sharma, accused of killing his wife Naina Sahni, she provides the background, with details that led to the incident, tying it up with a prediction of a seer who had told Sharma way back in time, that a woman would get him ill fame. It is in these instances that you see how the author has tied all strings together, fleshed all the information and presented it to the reader.

Behind Bars has garnered a lot of attention because of stories of high-profile prisoners. But, Choudhury has remained true to her concept of highlighting a diverse mix of cases. She says:

So, what was initially meant to be a how-to-survive-in-jail guide of the unlikely, influential and wealthy prisoners like Anca Verma, A. Raja, Pappu Yadav, Peter Mukerjea, Amar Singh and Somnath Bharti, also took on the need to find out about the other jailed inmates. How could I write a book on prison life and not write about those who are powerless and without a voice or are wrongly incarcerated?

The different cases highlight the jail experience of a regular inmate and a VIP, both of which are obviously never comparable. Interspersed with these experience of the privileged are the stories of the underdogs, of those who do not have the means to fight, of the innocent who are left to these inhuman conditions because they have still not proven themselves innocent. These instances are also very touching.

Readers get to know and learn about some idiocrasies and dangers of life in jail. Take for example the “bladebaaz”, slashers who are ‘hired’ to give cuts to inmates. Mundane matters related to eating, working, and merely living in jail are so beyond the imagination of common citizens. What kinds of friendships and rivalries do inmates nurture? How do they sort out disputes amongst themselves? These stories depict life inside the jail. How inmates work for each other in order to earn money, how some maintain their lifestyles even while inside and so on. Behind Bars weaves in these elements as well.

Almost all stories underline the pathetic living conditions in prison. In ‘The American Mallu who Survived Jail’, she talks about JP, an NRI, who was arrested on a drug-related charge. His story illuminates the horrendous conditions in the prisons, and gives a cringing account of his experiences.

‘From a rich life, I was transported to a black hole. The toilet was full of goo, so much so that when I was lifting my feet off the ground, the black peanut butter lifted off my feet.’

How did Choudhury get access to all this information? As an investigative journalist, it is very much a part of the job. But, what is commendable is how she has done her homework well, substantiating every story with facts. She has even talked to other inmates in prison in order to support or contrast the claims of her interviewee. For example, in a chapter on Amar Singh, she includes references from his fellow inmate Kobad Ghandy. She mentions in the book, about how prisoners themselves revealed a lot of information about the bending of rules in prisons:

If they hid their own comforts of how rules were bent for them, they didn’t hesitate to talk about others and, in return, the others filled in on their jail antics.

Common people find it fascinating to hear the ‘inside’ story. What happens behind bars, away from prying eyes? The voyeuristic in us wants to know the torments or victories of the games that go on within the guarded walls of Indian prisons. There is a lot of scoop here too, all presented boldly and fearlessly. But, the human angle behind it makes the reader think deeper.

There are some conspicuous instances that remain with you long after you finish reading Behind Bars. For example, the story of Wahid who recalls much torture and also the fact that he spent some time in a cell that had hosted Kasab or the deep friendship between Afzal Guru and Kobad Ghandy. Given the strong appeal of the recency effect, Peter Mukerjea’s account seems to be quite interesting.

If there’s one thing any jail teaches a white collar man, it’s how to make do on an impossible budget. It’s one of the first things that Peter says he learnt. ‘The economy within the jail is unique given there’s no cash – but a really effective barter system seems to work. Home-cooked food is a rarity and is therefore a prized possession for those that have it. There are all kinds of services available from a savvy barber, a masseuse, a yoga class that’s fully functional, a laundry service, a darzee (tailor) and lots more. Necessity being the mother of… is a well-trodden path here and adaptability and innovation is phenomenal. I get a monthly spending allowance of a princely sum of 2500 rupees, which I get each month from home by money order and which is credited to my ‘tuck-shop’ account and I get to buy goodies with that – biscuits, nuts, mineral water and such like, but making that last the month is an incredible challenge. So when I get out, I’m going to look forward to existing on a pocket money of 2500 per month and make do just fine.’

Or, another comment by another inmate who clearly marked the difference between haves and have-nots in jail…

As one said, ‘Subrata Roy is perhaps the only one in the history of Indian jails to have an air-conditioner. Moral of the story: If you steal 1,000 rupees, the hawaldar will beat the shit out of you and lock you up in a dungeon with no ventilation. But if you steal rupees 55,000 crore, then you get to stay in a 40-foot cell which has four split air- conditioning units, internet, fax, mobile phones and a staff of 10 to clean your shoes and cook your food (in case it is not delivered from Hyatt Regency that day)!’

Even as you hear the stories of supposed ‘criminals’, you cannot but help feel sympathetic towards the undignified and inhuman conditions in jails. More menacingly, these are accepted as common. These stories show that power games continue irrespective of court judgements or public opinion.

What the book highlights glaringly is stated quite simply: The thing about being freed after spending years in jail is that your life never becomes normal. Even someone like Amar Singh, otherwise quite open to the media, was reluctant to talk about his jail experiences with the author. He says:

“Those days were very painful and I don’t want to talk about them. You see, I’m not the man I used to be”

What finally emerges is how life in prison is a microcosm of life outside it. Truth, judgments and opinions aside, this book is perhaps a poignant reminder that civil society needs to take stock and responsibility of what happens ‘Behind Bars’.

The Lotus Collection, An imprint of Roli Books Pvt. Ltd, 2017